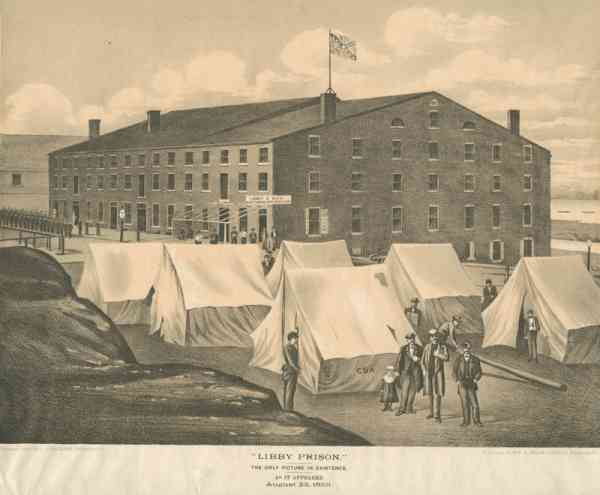

LIBBY PRISON

Libby Prison was one of the famous prisons located in Richmond. The Libby building, the only building in the area to have running water, was considered an ideal site by the Confederate authorities. The building was formally the Libby & Son Ship Chandlers & Grocers. It was somewhat isolated and could be easily guarded. Situated in a neighbourhood that had several warehouses, a number of shanties, an old meeting house, several stables, and numerous vacant lots. The site was accessible by both railroad and water transportation, bordered by the James River, and was away from the congestion of downtown.

The building was 3 stories at the front, 4 stories in the rear, and measured almost 45,000 square feet. It was about 135-feet wide and extended 90- feet back. The inside was divided into 3 sections by thick walls that extended up from the basement to the roof. This gave the appearance from the back that the building was made up of 3 smaller buildings built side by side. Each story was divided into 3 low, oblong rooms measuring 45x90 feet, with exposed beams. There were 100 prisoners in each room. The prisoners were to occupy the 2 upper floors, or 6 upper rooms. At each end of these rooms were 4 small windows. It was arranged for all of the windows and doors to have flat-iron bars installed over them and makeshift water closets to be built on each floor. The middle room on the 1st floor was to be used for cooking. The kitchen was the only place in the building that a prisoner could have free access. The east room on the 1st floor was used as the hospital.

The west room was to be used as the quarters for prison officials, and the basement was divided into dungeons for the confinement and punishment of unruly prisoners. The prisoners were not allowed to go within 3 feet of the windows. The rooms did not have any furniture, the ventilation was poor, and the lighting was gloomy. Although the prison had running water, the water used by the prisoners was taken from the river, which was usually of poor quality.

Lt. Thomas Pratt Turner was the prison's first commandant. He would eventually be despised by the prisoners. The second in command was Richard R. "Dick" Turner. He quickly attracted the hatred of the prisoners because of his haste in using physical punishment. He was also known to kick the dying prisoners for no apparent reason when he found them lying on the floor. The third in command was George Emack, who later received a Lieutenant commission. He was as ruthless as "Dick" Turner and was equally hated by the prisoners. The prison clerk was Erasmus Ross. He was in charge of recording the prisoner's names upon arrival and conducted the daily roll calls. He, too was hated by the prisoners. The prison was guarded by 2 companies of 30 soldiers each. There were 30 guards on duty at all times. The guards lived in tents on the vacant lots nearby.

The first group of prisoners arrived on March 26, 1862, when more than 500 prisoners came from Richmond's surrounding prisons the first registered prisoner was Mr. Philander A. Streator of Holyoke, Massachusetts. The prison grew to 700 only after 3 days after opening, and another 600 political prisoners were added a few days later. 10 They were soon moved out due to sev e r e o v e r c r o w d i n g . The prison was briefly used as the main hospital for all of Richmond's prisoners in the summer of 1862. By autumn of 1863, conditions at the prison became so bad that many of Richmond's former prisons were now being used as prison hospitals.

Libby, serving as the headquarters for the Confederate States Military Prisons since the first of the year, 1863, was the depot prison to which all prisoners were brought before being transferred to other facilities in or outside the city. Each day more prisoners were brought in than would leave, thus increasing the prison population at Libby. After a short lull during the prisoner exchange program, the population quickly rose to over 4,000 and was never less than 1,200 prisoners on each floor, or an average of 400 to each room.

LIFE & CONDITIONS:

By 1863, the rooms became so crowded that the prisoners had to sleep "spoon-fashion". They were head to foot in alternating rows along The floor. They were packed so tight that when they slept, it became the responsibility of the highest ranking man in each room to call out "spoon over!" throughout the night to enable everyone to roll over in unison. Prisoners complained of short rations, cold, and lice, yet many were able to buy extra provisions and receive packages from home. The prisoners suffered from the intense cold weather. The windows at the prison were broken out during the summer for relief from the heat, and now the cold weather came in the broken windows. Smallpox and diseases were increasing dramatically. Black servants (captured Northerners) served the white officers, and there was running water and even primitive flush toilets. Still, inmates' letters fuelled Northern reports of inhumane conditions, especially after sentries were ordered to shoot anyone appearing at the windows, and hundreds of pounds of gunpowder were ominously placed in the cellar following a mass escape early in 1864. Confederate authorities tried to head off negative opinion by inviting in outside observers. They reported plentiful that 11 books, games of whist, and classes in Greek. There were, however, many activities that the prisoners did engage in during the daytime. Chess was the most popular pastime, with there being chess tournaments. The prison became one of a number of prisons that had a prison newspaper, the Libby Prison Chronicle.

By 1863, the daily rations were getting smaller. A daily ration then consisted of a couple of ounces of meat, 1/2 pound of bread, and a small cup of beans or rice. Many escapes occurred. The most spectacular was one, led by Col. Thomas E. Rose (77th Pennsylvania Volunteers) assisted by Maj. A.G. Hamilton (12th Kentucky) on February 9, 1864, in which 109 officers tunnelled their way out. 48 were recaptured and 59 were able to reach Union lines, but 2 drowned. Rose was one of the unlucky, finding himself back in Libby. He was later exchanged on April 30, 1864. The only tools which they had to use in the long tunnel digging were an old pocket knife, some chisels, a piece of rope, a rubber cloth and a wooden spittoon. They constructed the 53-foot long tunnel in 17 days.

By 1864, the conditions in the prison continued to get worse. Half of the prison's 76 windows were without glass in them. Wood rations were limited to only 1 or 2 armloads a day. Each room had only 2 stoves and held about 400 prisoners. There was an increase in illness among the prisoners. Scurvy, chronic diarrhoea, dysentery, and typhoid pneumonia became the most prevalent diseases and, before long, 2 or 3 deaths a day were not uncommon.

The dead bodies were placed in the west cellar. The bodies were allowed to accumulate until a full wagon-load was obtained. The bodies were taken to Oakwood Cemetery for burial.

Miss Elizabeth Van Lew, the Union agent in Richmond, was a frequent visitor to Libby, bringing food and reading material. It is stated that she obtained much valuable information from the men there and passed it through her efficient agents to the Union. She is also credited with arranging for a number of men to escape, though no tunnel existed between the prison and her Church Hill home, as has been said.

On April 2, 1865, Richmond was under orders to evacuate the city. The Union troops were upon the city and all of the prison commandants were to evacuate their prisons, leaving back only the sick and prisoners too weak to move. Maj. Thomas Turner was the last man to leave the prison, burning as many prison records as possible. By 3:00 A.M. on the April 3, Richmond was abandoned and in flames. Nearly all of the tobacco factories and warehouses used to confine prisoners were destroyed by the fire.

When Richmond fell into Union hands, up to 700 Confederates were gathered from around the city and confined at Libby Prison. Only Libby and Castle Thunder survived the flames that burned most of the city.

The above article first appeared in the ACWS Newsletter, Automn 2009